Alphonse Mucha was born in 1860 in Ivačice, in what is now the Czech Republic. A fervent patriot and supporter of the political liberty of the Slavic peoples, he devoted himself to art,

moving to Paris in 1887. There, he refined his craft and met the woman who would change his life forever: Sarah Bernhardt, the most beautiful and renowned actress of the time. Upon trusting her

image to Mucha, she ensured his great popularity.

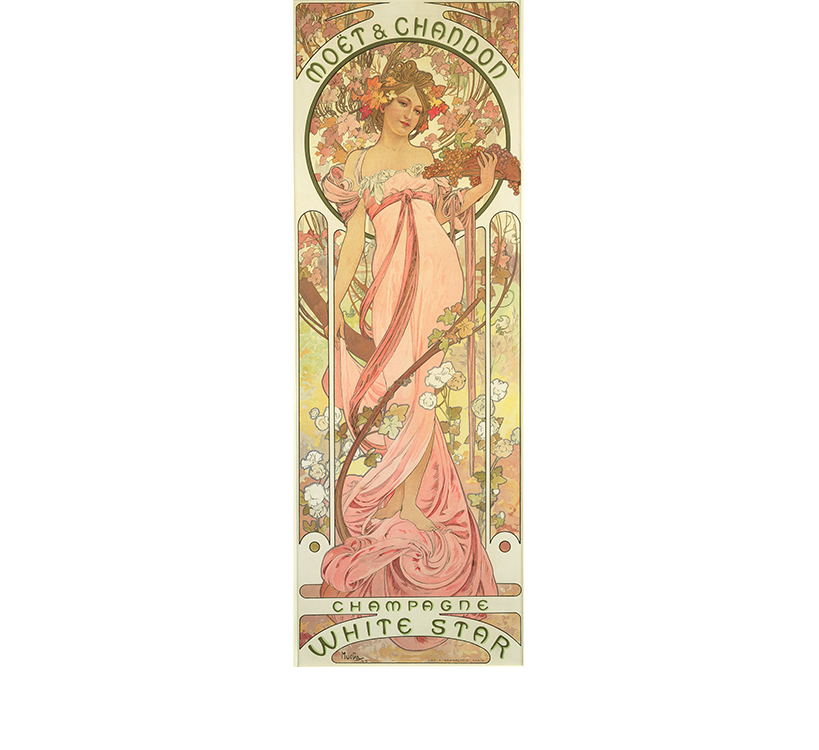

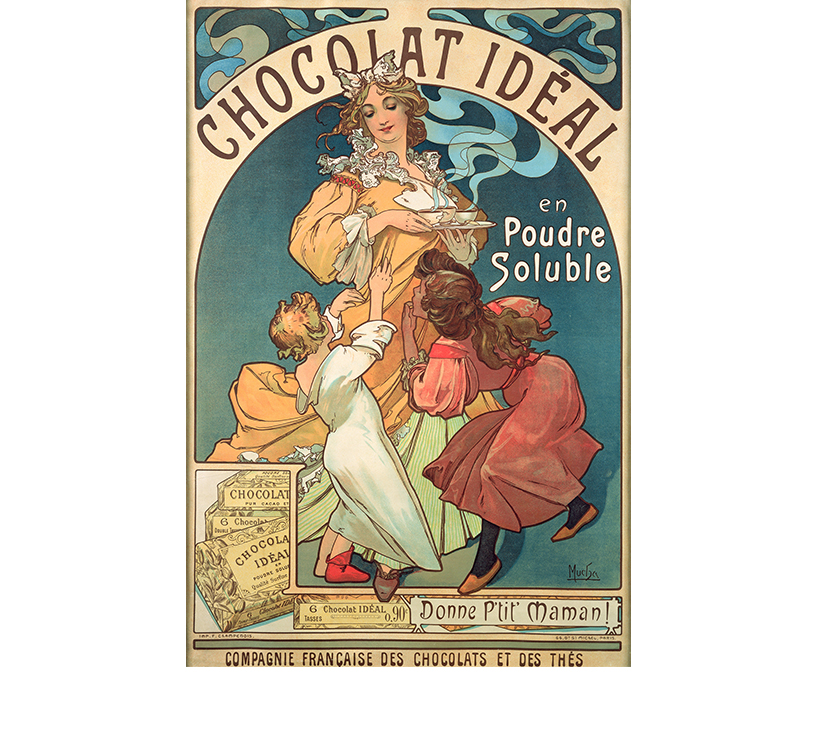

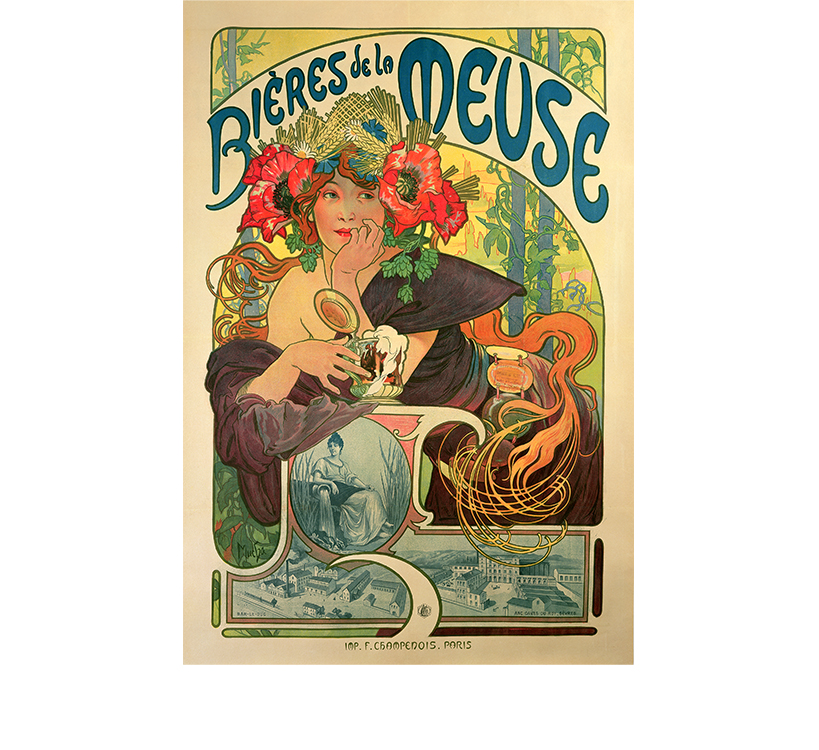

The legend of “Mucha’s women” was born, and companies vied for him to help market their products, giving rise to enduring advertising campaigns like the one for Nestlé Baby Food and Moët

& Chandon champagne, in addition to cigarettes, beer, biscuits, and perfumes. However, Mucha did not neglect his patriotic and social commitment. In 1910, he returned to

Prague and devoted nearly twenty years to what is considered his greatest masterpiece, The Slav Epic: a colossal work composed of twenty enormous canvases recounting the main events in the history of the Slavs.

Mucha died in Prague in 1939.

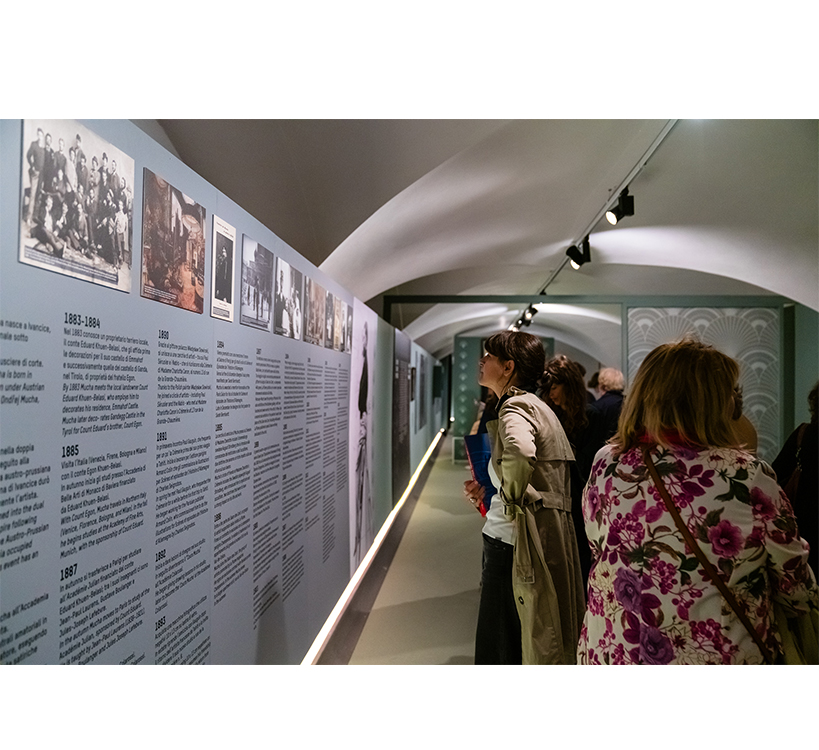

THE EXHIBITION

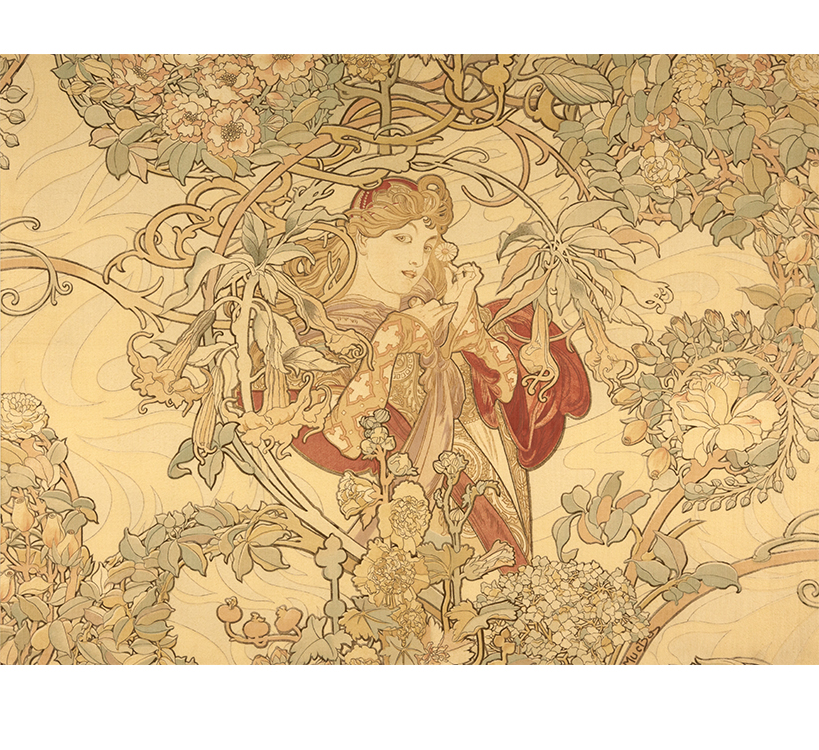

At the turn of the twentieth century, Paris was considered the centre of the art world; and during this time of great excitement, the time of the Belle Époque, Alphonse Mucha became the era’s most renowned and controversial artist. His works, illustrations, theatrical posters, and early advertisements ushered in a new form of communication. His art immediately became world famous and his style the most widely imitated. The powerful beauty of his women entered into the universal collective imagination.

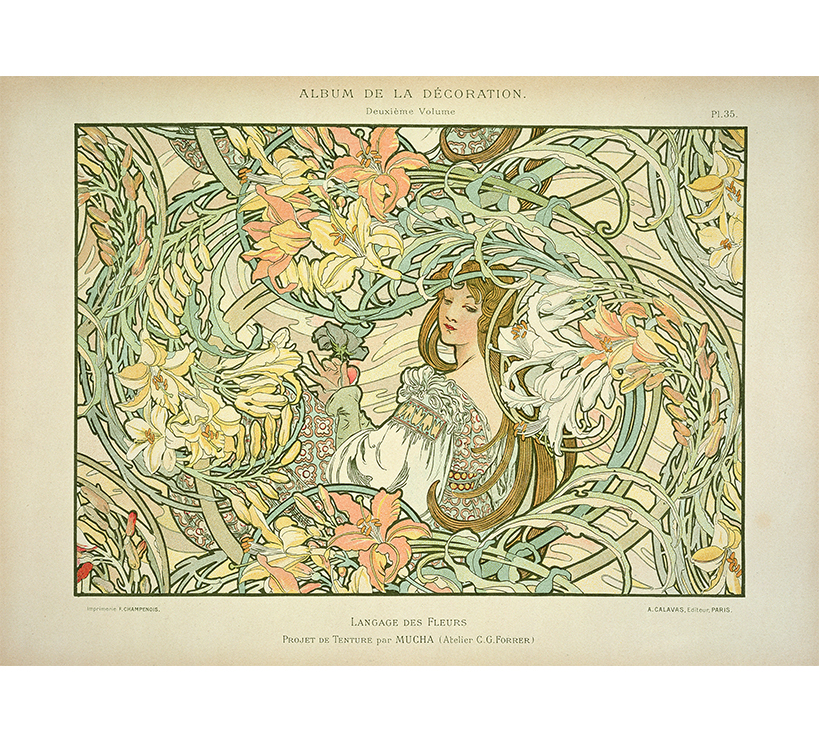

It is the gaze of a new woman claiming her rights to the freedom and dignity that had been denied her until then. It is the beginning of modernity, for which Mucha – with a language influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, by Japanese woodcuts, by the beauty of nature, and by Byzantine and Slavic decoration – became the spokesman. It is a new art also in design. Starting from observation of nature, Mucha availed himself of the new scientific knowledge, which he would define as “theories on how to enchant,” the mechanisms of visual perception (eye-nerves-brain). To determine what the most pleasant shapes and lines are, he suggested learning the law of balanced proportions from the organic structures of nature:

“Visible nature, seen through our eyes, surrounds us with rich and harmonious forms. The marvellous poem of the human body, those of animals, and the music of lines and colours emanating from flowers, leaves and fruits are the most obvious teachers of our eyes and taste.”

The exhibition also includes a section dedicated to the development of the new artistic language in our country: an homage to the Florentine Galileo Chini, one of the leading practitioners of Art Nouveau in Italy.

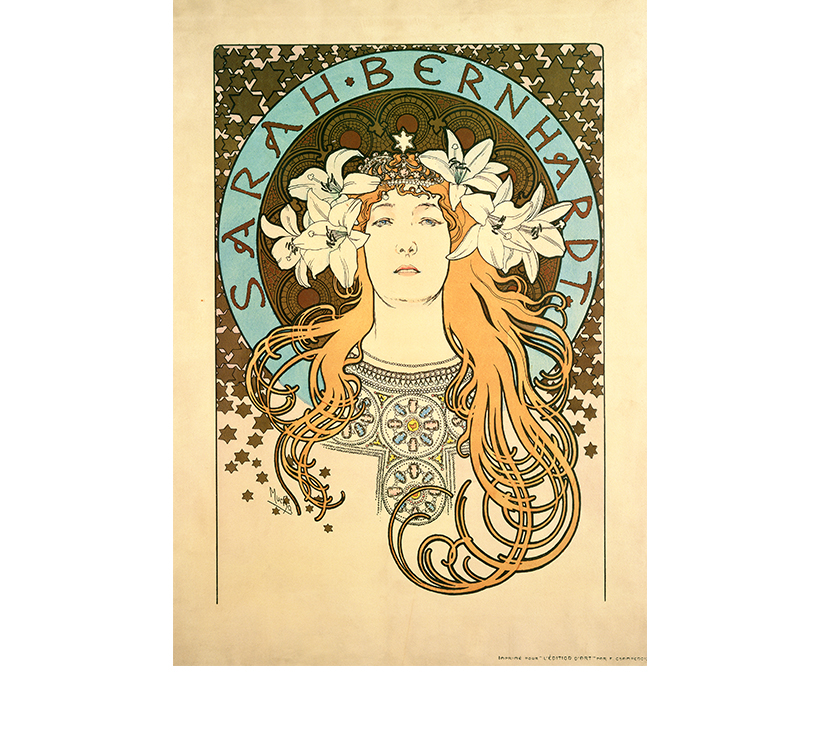

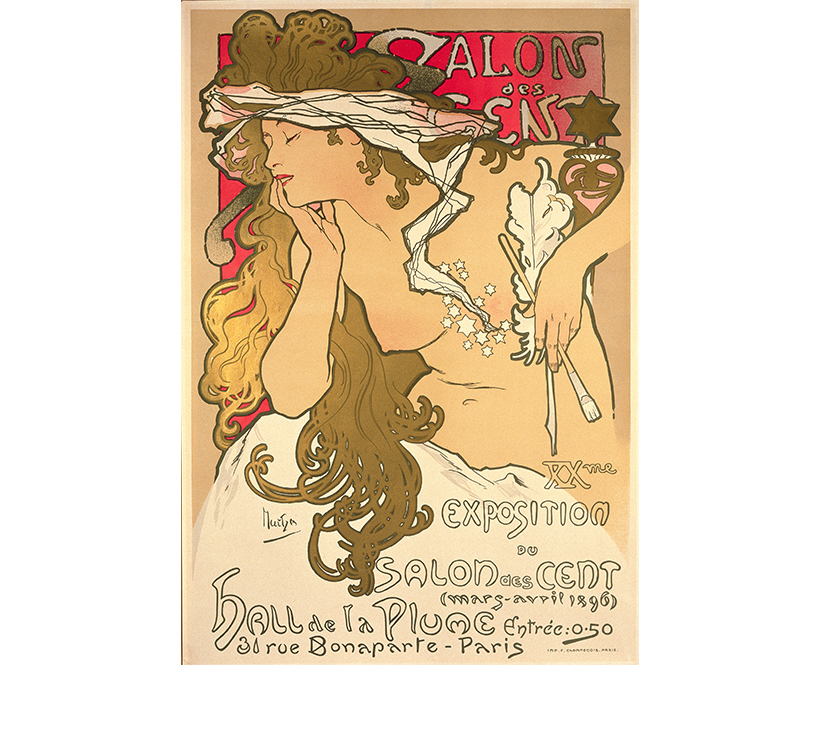

First section – Women, Icons and Muse

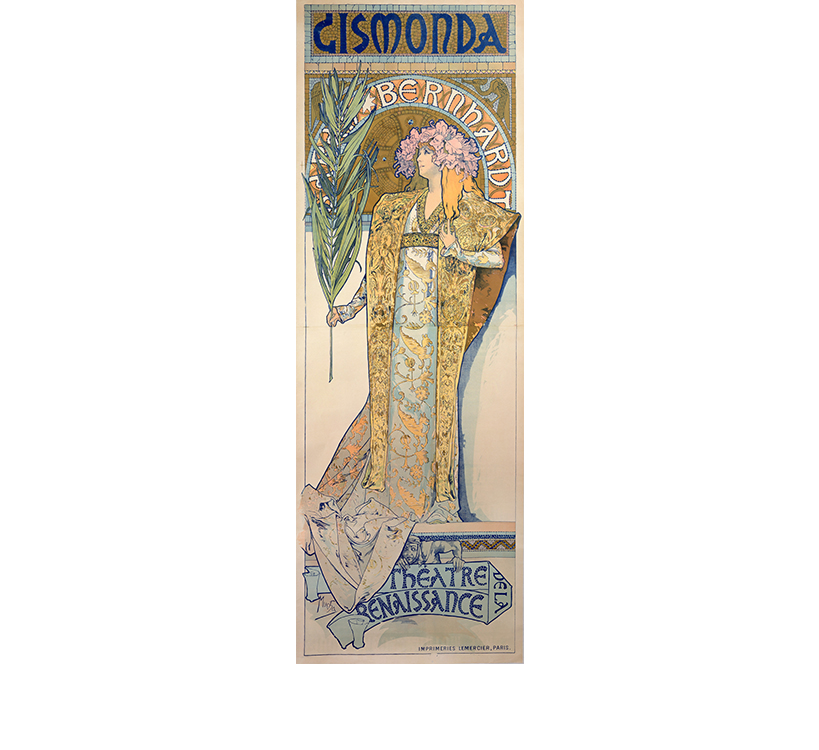

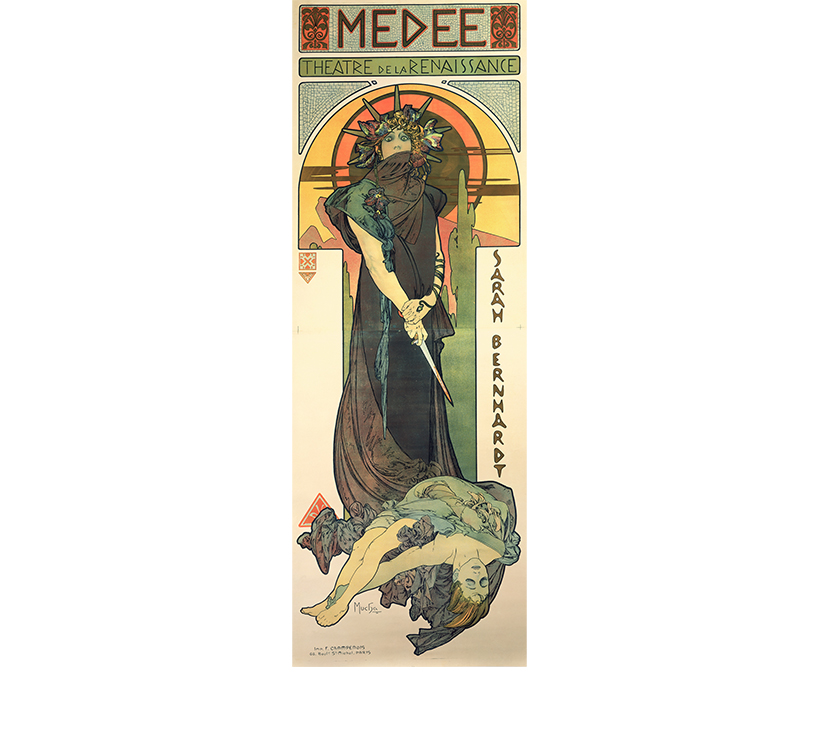

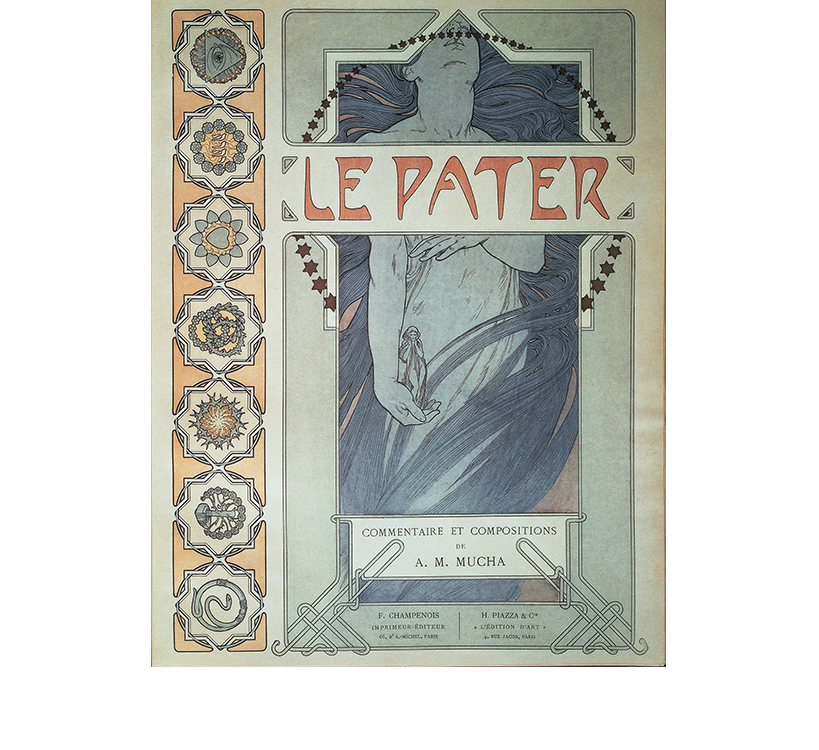

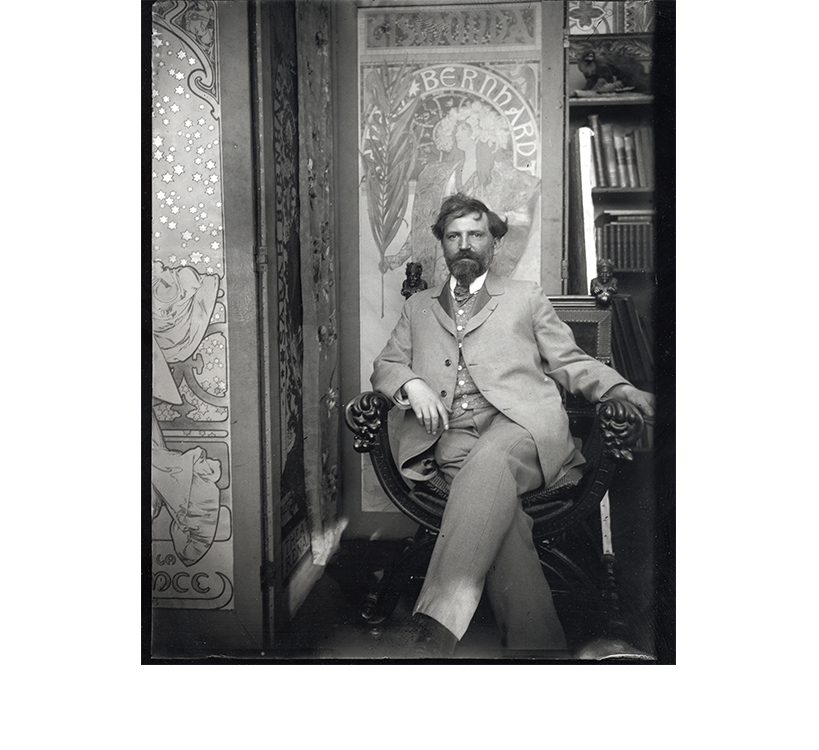

Women are the cornerstone of Mucha’s art. Beautiful, voluptuous, and sensual yet innocent at the same time, they presented the antithesis of the image of the decadent, dangerous woman depicted by late-nineteenth century artists. In fact, it is because of a woman, the world-famous Parisian actress Sarah Bernhardt, that the Mucha style came into being. The Czech artist met the great actress in late 1894, when she commissioned him for the poster to promote the play Gismonda. While Mucha was at that time a fairly successful book illustrator, he was entirely unknown in the field of advertising posters. In spite of his inexperience, the “Divine Sarah” was struck by the originality of his compositions in natural size, an unusually tall format marked by fluid, elegant contours and velvety pastels. The power of Mucha’s work lay above all in his ability to portray the soul of the characters Bernhardt was to play. His posters did not simply resemble his muse, but they transmitted the self-image that Bernhardt aspired to bring to the stage. Unveiled on Parisian billboards on New Year’s Day in 1895, this first poster for the “Divine Sarah” enraptured the city. The success led Bernhardt to offer him an exclusive six-year contract not only as designer but also as artistic director for the works she acted in and produced. Mucha would design costumes, jewellery, and sets for the actress, along with six posters that would make Sarah Bernhardt an everlasting icon.

Recognizable, captivating, and within everyone’s reach, the Czech artist’s advertising posters defined the “style Mucha,” whose recurring characteristics would become key elements of Art Nouveau.

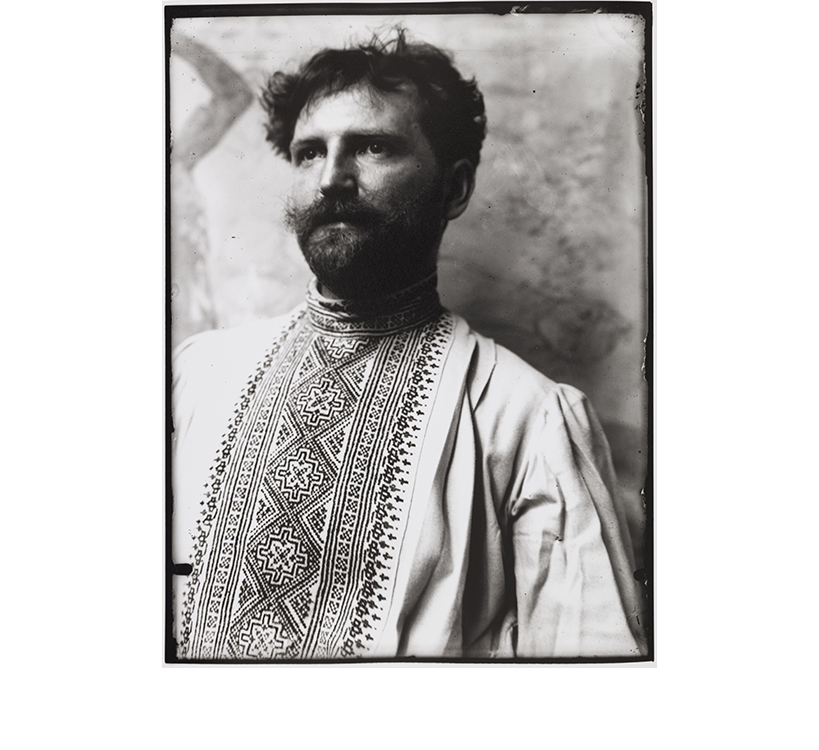

Second section – Breton culture

Mucha saw art as the expression of a people’s cultural and ideological identity; he frequently depicted himself wearing an embroidered Slavic folk shirt, a symbol of Slavic unity. His works were dominated by traditional elements of the motherland, seen in the form of garments in Slavic style, floral and botanical motifs inspired by the arts and crafts of Moravia, circular motifs reminiscent of haloes, and the curves and geometric themes of Czech Baroque churches. Mucha infused new life into age-old symbols and decorative motifs, integrating them into an exquisitely Czech context. For Mucha, ornamental motifs were alphabets of visual languages destined to evolve and to bear a universal message of union between past, present, and future.

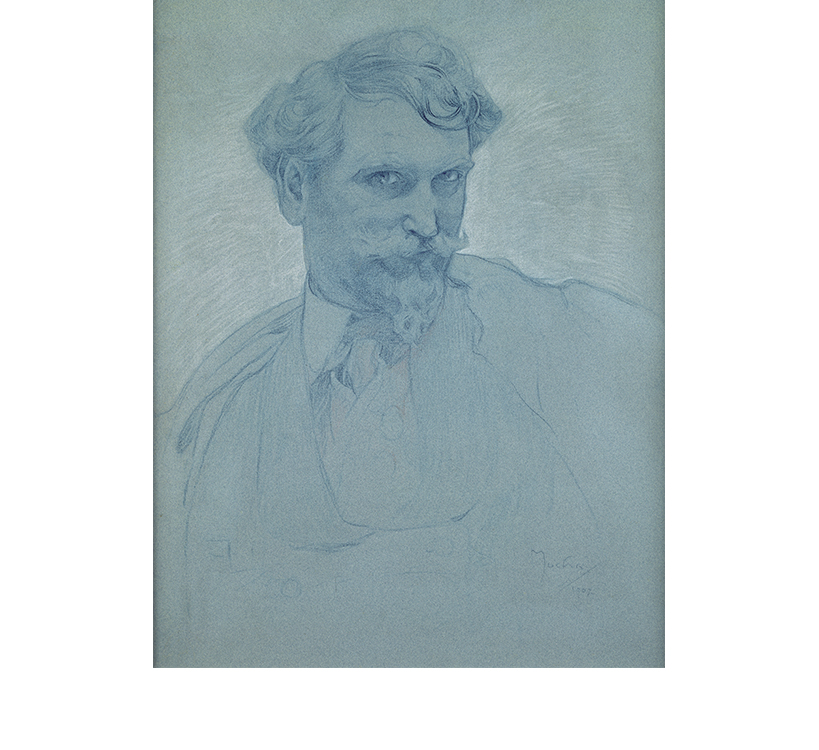

During the years he spent in France, the artist recognized a profound affinity between Celtic and Czech popular cultures; he developed a passion for traditional Breton culture, and often ventured to Brittany to observe it first hand.

Mucha’s travels in Brittany during this period are documented by numerous sketches and photographs of the local landscapes and popular culture, and in particular of the various decorative styles and popular costumes typical of the region.

Breton folk images were iconic subjects for many other painters, including Paul Gauguin, with whom Mucha had a deep bond. Their friendship would continue until Gauguin left for Tahiti permanently.

Third section – Advertising posters

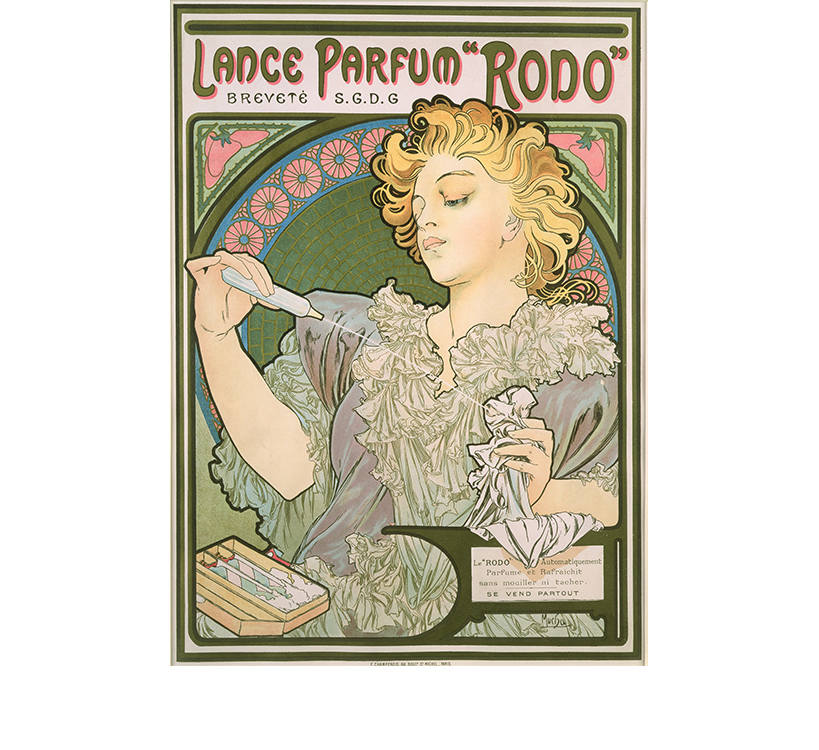

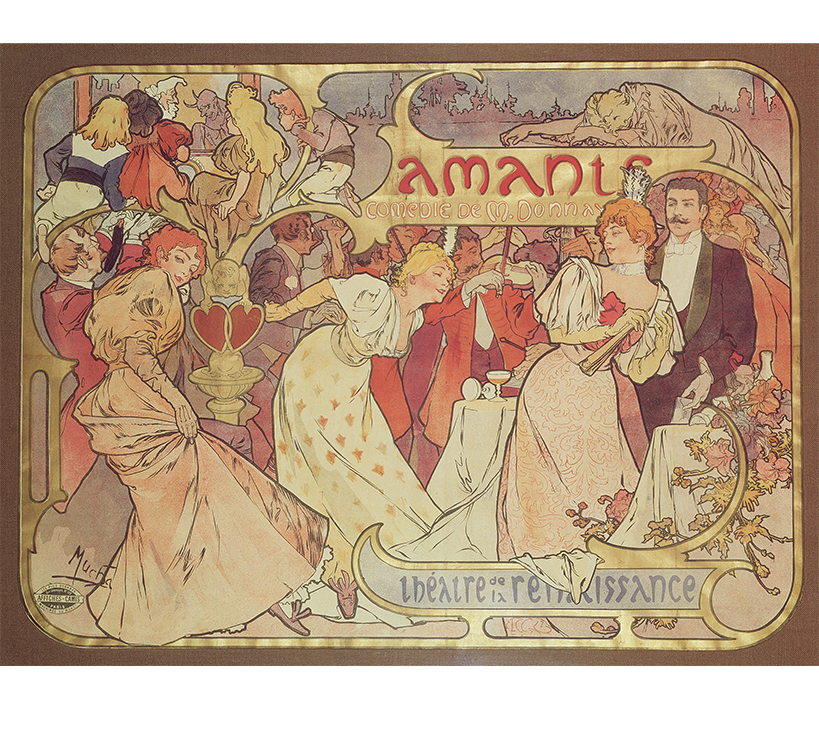

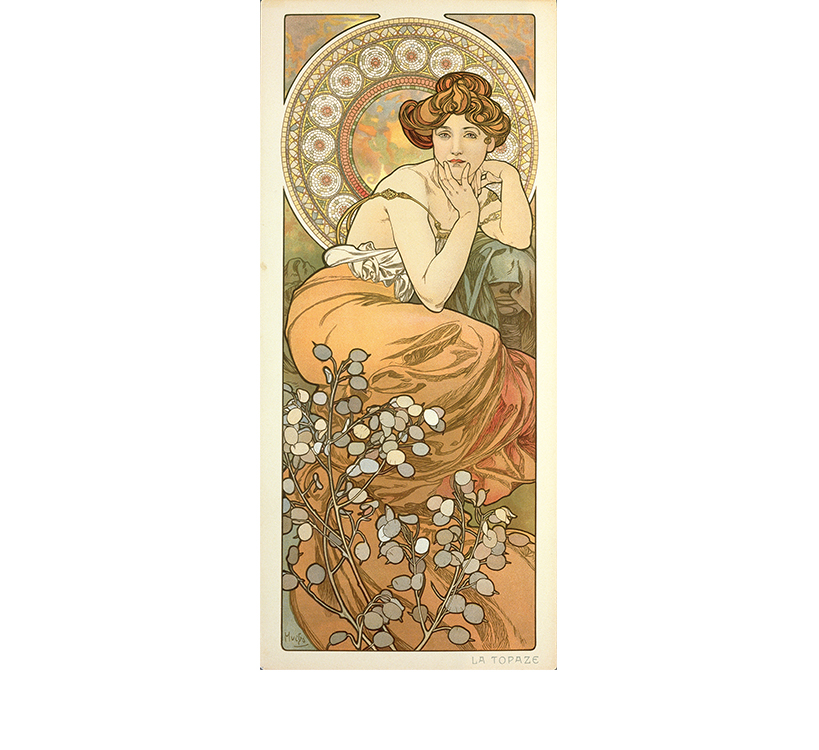

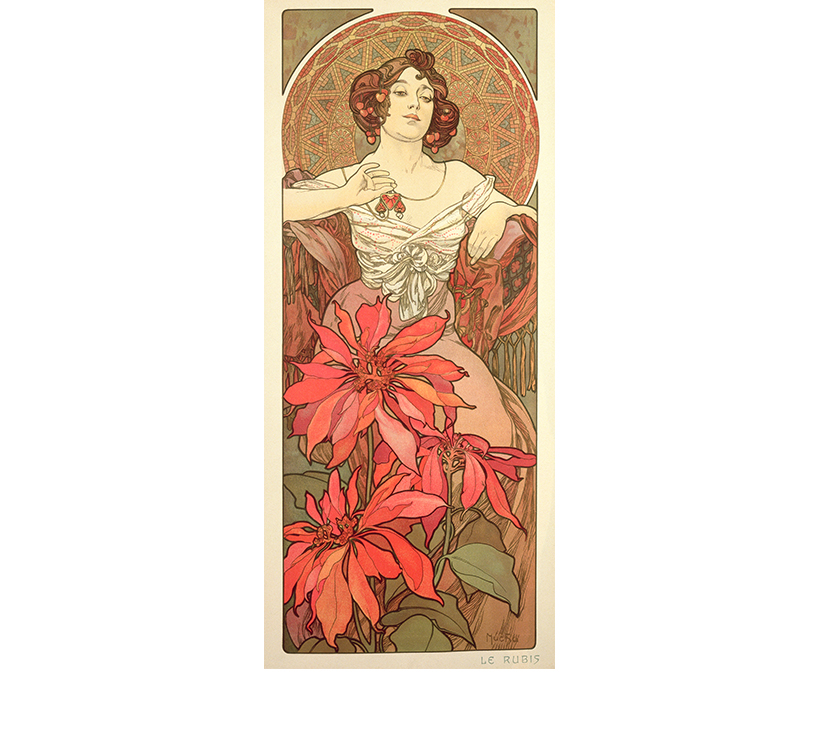

Over the course of twenty years, Mucha designed and executed about 120 posters, many of which now considered genuine icons of Art Nouveau. The Czech artist became the leading figure in poster design, as well as the graphic designer most emulated and in demand in late nineteenthcentury Paris.

Art and advertising, according to Mucha, have the common goal of transmitting a message to the public; whether it is a message for a commercial product or a sacral, religious, or historic message makes no difference. For the artist, advertising activity was the ideal terrain upon which to explore new, effective modes of communication. Whether it was a matter of alcoholic beverages, champagne, beers and spirits, or of detergents, perfumes, bicycles, and cigarettes, the advertised item receded into the background, while it was always an idealized, elegant young woman that took centre stage. Hieratic female figures framed by dynamic graphic contours evoked seductive atmospheres and, with their captivating smile and enchanting gaze, enticed the viewer to enter into their world.

These female figures represented beauty, grace, and elegance, creating the sensation that the offered products came down from heaven, borne by sacred maidens. The colours, too, were innovative, chosen mostly among pastel hues with delicate nuances, for a considerable visual impact. Mucha arranged the images on a number of perspective planes, overlapping several decorative layers, each intricately detailed. This overlapping of layers contributed to the visual complexity of his works, creating a sensation of depth.

Fourth section – The Slav Epic

In 1910, Mucha returned to his native country after a 25-year absence, to realize his life’s dream: to serve his homeland with his art.

During one of his numerous journeys to the United States, he met Charles Richard Crane, a wealthy businessman and a keen Slavophile who grew enthusiastic over the artist’s vision of a new Europe and decided to support him financially. From then on, Mucha would be able to devote himself freely to the creation of The Slav Epic, a monumental masterpiece with a messianic message inviting the Slavic people to learn from its history in order to progress towards the future and freedom. During those same years he worked on other public projects, including the interiors of Prague’s city hall, the design of a stained glass window for Prague’s Saint Vitus Cathedral, and posters for the Sokol movement’s pan-Slavic gymnastics competitions.

The Czech artist continued to develop the Mucha style as a universal visual language. The figure of the woman remained the central element, becoming a spiritual icon in traditional ceremonial dress, the “soul of the nation” inspiring and uniting the Slavic peoples.

Among the finest examples of these works is the cycle’s final canvas, The Apotheosis of the Slavs. In this elaborate composition, Mucha expresses his own vision of Slavic history as a homogeneous movement: a spiral of continuous historic events surrounding the current condition of the Slavic peoples after the victory of 1918, shown at the centre. Radiating from this celebratory event are the curved lines of ribbons and rainbows directing the viewer’s gaze towards the future apotheosis, in which these peoples, symbolized by the figure of a flowering youth and by the dazzling light of hope protected by a young woman in white, will contribute towards the progress and peace of humankind.

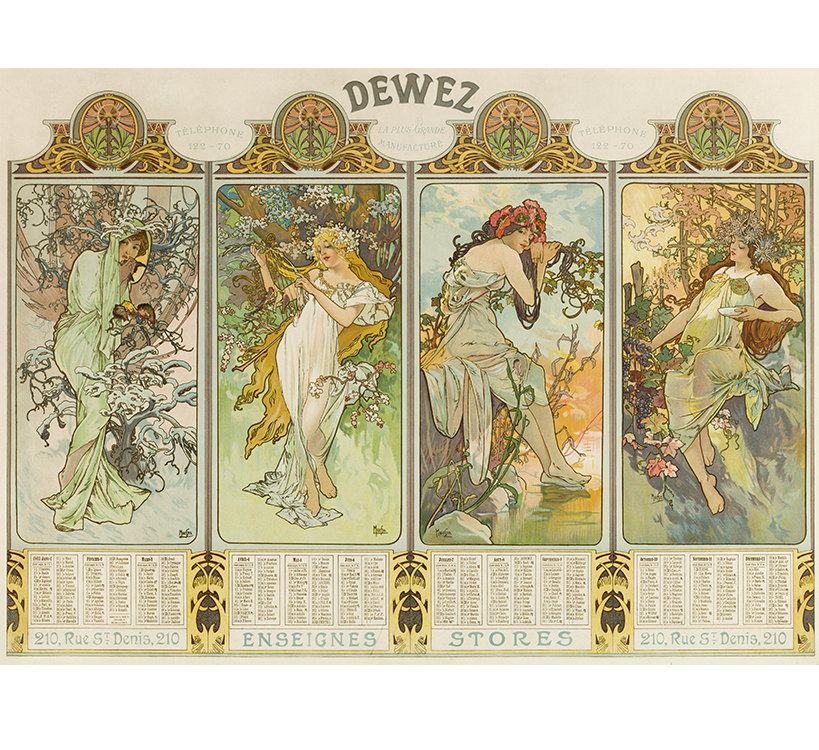

Fifth section – Style Mucha

The rise of modernism led to revolutionary changes in how art was conceived – but on this point Mucha’s thought conflicted with the atmosphere in Paris during those years. The Czech artist rejected the idea that art could change; for him, it had an immutable and universal value. He wrote: “Art can never be new. The idea of ‘modern’ art as a passing fashion is offensive. Art is eternal like mankind’s progress, and its function is to light the way for the world. Art is constantly developing, and is always a few steps ahead of humanity.” The Czech artist had the firm conviction that a beautiful work was the “symbol of goodness,” helping to lift the public’s soul and in the end generating a better society.

The graceful forms of the female body and the sinuous lines of nature guided the viewer’s gaze towards the composition’s focal point. Everything was conceived to attain understanding of “beauty,” the only way to raise the quality of life.

Mucha favoured simple and universal themes like the seasons, flowers, and hours of the day – themes easily comprehensible also to the layman, and that can thus inspire the seeking of beauty. Mucha’s works, from drawings to decorative prints, would then be offered in a myriad of forms, like calendars, postcards, and even everyday items, and reproduced in a host of art magazines in France and abroad, thus spreading the style Mucha everywhere. Now very much in fashion, his style would influence the entire Exposition Universelle of 1900.

Sixth section – Art Nouveau in Italy

Mucha’s innovation of a visual language, made unique by the wholly new conception of decoration inspired by nature, with the expressive use of the line in motion, free compositions, and a fascination with the female figure, mirrored the spirit of the art simultaneously spreading in the leading European capitals beginning in the late nineteenth century. The Czech artist’s works embodied the principles of the great ferment in Europe at the turn of the century, and helped shape the stylistic model of Art Nouveau by redefining the concept of beauty. The rhythmic and elegant movement of maidens with long, flowing hair, the ample and swirling drapery, and the dynamic decorative mark became a suggestive model for modernist artists, especially in the field of decoration and applied arts. Although lagging slightly behind, Italy also embraced the need to give life to a stylistic and iconographic model capable of interpreting contemporary modernity. The aethereal maiden, graceful and harmonious in her movements as so often immortalized by Mucha, came to symbolize the imagery of Liberty – the Italian version of Art Nouveau – in the poster designed by Leonardo Bistolfi for the Prima Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte Decorativa Moderna (First International Exposition of Modern Decorative Arts) in Turin in 1902 – a key event in the explosive spread of the new, modern artistic language in our country that marked “Italy’s official entrance onto the European stage.”

Alphonse Mucha. The Seduction of Art Nouveau Venue Museo degli Innocenti, Piazza della SS. Annunziata,13, 50121 Firenze Dates open to the public 27 October 2023 – 7 April 2024 Opening hours Every day from 9.30 a.m. to 7 p.m. The ticket office closes one hour earlier Tickets Exhibition + Museo degli Innocenti Full price € 16,00 (audioguide included) Reduced price € 14,00 (audioguide included)